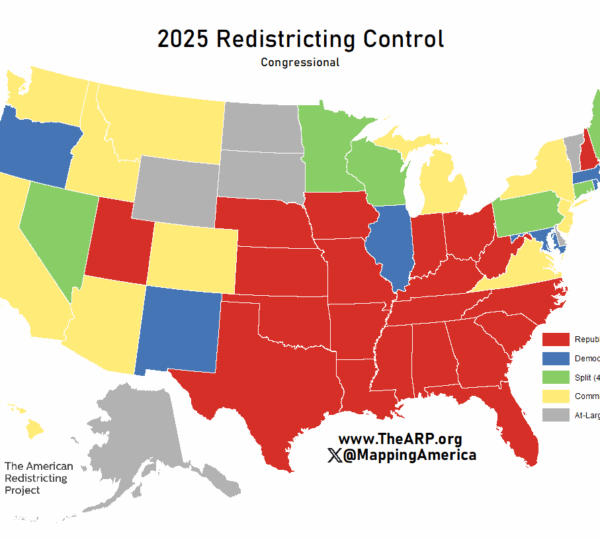

Away from campaign rallies and televised debates, the political map of the United States is being reshaped through a quieter but increasingly consequential process.

District lines—often revised with little fanfare and minimal attention from the broader public—are once again at the center of the balance of power, subtly altering the terrain on which future elections will be fought and, in some cases, reshaping representation far more dramatically than a single campaign speech ever could.

Every decade, following the U.S. Census, the 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives are reapportioned among the states based on population changes. But redistricting — the act of redrawing district lines — plays out on a timetable and in a political context that can extend far beyond that once‑a‑decade rhythm.

While the census provides the data that typically triggers redistricting, in the current political moment lawmakers in several states have moved to redraw their districts mid‑decade — a highly unusual and controversial step that has intensified partisan conflict nationwide.

The Stakes of Redistricting in Today’s Political Landscape

At its core, redistricting is supposed to reflect population changes — to ensure that each person’s vote carries roughly equal weight.

But the way lines are drawn can influence which party is more likely to win seats, sometimes for many election cycles. This has made redistricting a strategic tool more than a mere administrative task.

In states such as North Carolina, Texas, Missouri, and California, the process has taken on starkly political contours.

What appears at first glance to be technical map drawing has become deeply strategic, with each party seeking maps that lock in advantages and insulate elected officials from the normal ebb and flow of public opinion.

For example, Republican‑controlled legislatures in states like North Carolina, Texas, and Missouri have adopted new congressional maps in 2025 designed to increase their party’s share of U.S. House seats.

In Texas, Republican lawmakers approved a plan that was intended to add up to five new Republican‑leaning seats for the 2026 elections, even though the state’s overall population is politically more competitive than its current delegation suggests.

Measures like this matter because the House majority can hinge on just a few seats. If a party can reliably secure extra seats through district lines, that can translate into legislative power regardless of whether [its candidates won a majority of the overall votes across the country].

Even a small gain — one or two seats — could determine whether a president’s legislative agenda advances or stalls, tying local redistricting decisions directly to national governance and policy outcomes.

Mid‑Decade Redistricting: An Unusual and Controversial Trend

Traditionally, redistricting follows the census once every ten years. This is based on the principle that districts should reflect population changes captured by the decennial census. Mid‑decade redistricting — when a state redraws its districts before the next census — used to be rare.

According to analysis, only a couple of states voluntarily redrew maps between census cycles in the 52 years between the 1970s and 2024.

That pattern changed in 2025. Republican leaders in states like Texas, Missouri, and North Carolina moved forward with mid‑decade redistricting plans aimed at generating extra House seats ahead of the 2026 midterm elections.

The push was explicitly tied to national political objectives: former President Donald Trump and other GOP leaders encouraged state officials to redraw maps to protect and expand Republican House control.

The Texas Legislature’s special session to redraw congressional districts, for example, came under direct pressure from Republican leadership in Washington.

Texas lawmakers approved a map that would shift several Democratic seats to Republican‑friendly configurations and potentially net the GOP up to five additional seats.

That map was then challenged in court as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. After judicial back‑and‑forth and a timing battle tied to candidate filing deadlines, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the redrawn lines to be used for the 2026 elections.

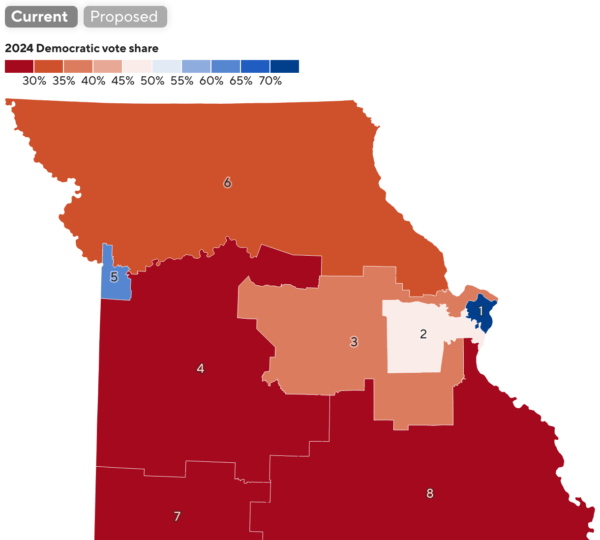

In Missouri, Republican officials also called a special session in 2025 to redraw congressional boundaries, with the new map passed and signed into law.

That map has been met with lawsuits and an efforts to collect referendum signatures that could suspend it until voters decide in a special election.

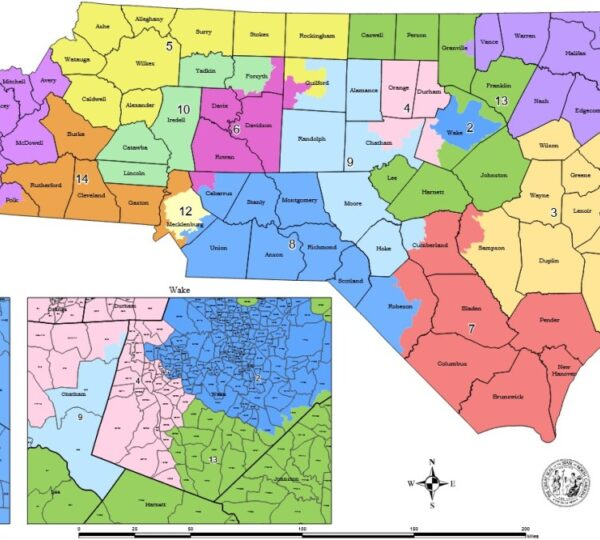

And in North Carolina, a federal judicial panel permitted the state to use a map that was designed to give Republicans a new seat by reshaping a competitive district.

Democratic Responses and the Battle in California

In response to this Republican‑led wave, some Democratic leaders have begun considering their own mapmaking strategies rather than relying on long‑standing reform principles like independent commissions. One of the most notable examples is California.

For years, California was held up by reform advocates as a model: the state’s independent redistricting commission was designed to remove legislators from direct control over line drawing, reducing partisan influence and increasing fairness in representation.

However, in 2025 voters passed Proposition 50, which temporarily altered that commission and allowed the Legislature to adopt new congressional maps intended to produce five additional Democratic seats for upcoming elections.